Welcome, students of history! This guide’ll explain everything you need to know about creating effective history outlines and turning them into polished papers.

History is more than memorizing dates and events.

It’s about understanding how and why things happened, analyzing cause and effect, and connecting the dots between different historical occurrences.

Organization is essential for communicating these complex ideas effectively.

Good history writing doesn’t happen by accident. It requires careful planning, thorough research, and a clear structure.

Whether writing a short essay or a lengthy research paper, starting with a solid outline is the key to success.

Many students struggle with history assignments because they dive into writing without a roadmap.

This approach often leads to rambling papers, missed arguments, and lower grades.

Taking the time to create a thoughtful outline seems like extra work, but it saves time in the long run and produces much better results.

By the end of this guide, you’ll have all the tools you need to confidently approach any history assignment. For additional support with your history assignments, you can also explore AI-powered tools at AI Homework Helper’s history resources.

Understanding the Different Types of History Assignments

Before you start outlining, you must understand what type of history assignment you’re working on. Different tasks require different approaches.

History Essays

Essays usually focus on answering a specific question or defending a particular thesis.

They’re typically shorter than research papers (5-10 pages) and rely on a clear, well-supported argument.

Essays often analyze primary sources, compare interpretations, or evaluate historical events.

History Research Papers

Research papers are more in-depth explorations of historical topics. They require extensive research, multiple sources, and original analysis.

These papers typically range from 10 to 20 pages and need a more detailed outline to organize the material.

They might examine a historical event, analyze a historical trend, or explore a historical figure’s Impact.

Historical Analysis Papers

Analysis papers focus on interpreting primary sources or historical evidence.

They require close reading of historical documents and critical thinking about their meaning and significance.

These papers are less about reporting facts and more about your interpretation of historical materials.

Historiographical Essays

These papers examine how different historians have interpreted a historical event or period.

They compare and contrast various perspectives and schools of thought within historical scholarship.

These papers require research into the historical event and how historians have written about it.

No matter which type of history assignment you’re facing, AI Homework Helper offers resources to assist with all academic writing challenges.

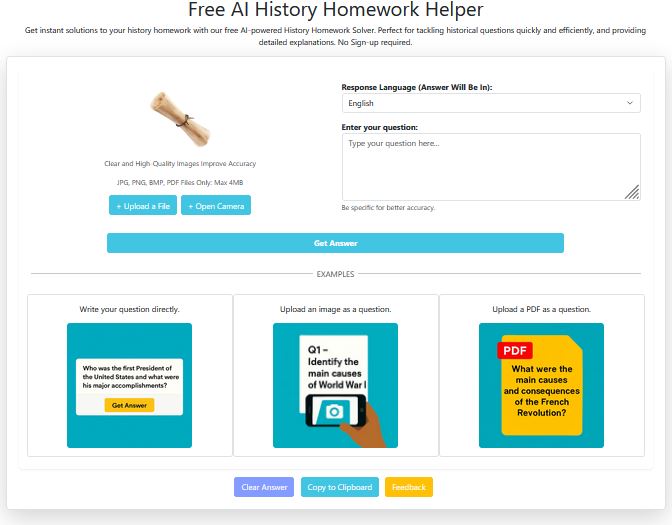

Solve History Homework Using AI

Before digging deep into the history subject challenges and its types of homework questions, if you want to get step-by-step answers of your history homework or assignment by simply uploading the image or pdf then Visit Website: Free History Homework Helper Tool.

Getting Started: Research Techniques for History Papers

Good historical writing begins with good research. Here’s how to approach this crucial step:

Start with Background Reading

Before diving into specific sources, get a general understanding of your topic. Textbooks, encyclopedias, and overview articles provide context and help you identify key areas to research further.

Find Primary Sources

Primary sources are materials created during the period you’re studying. They include:

- Letters, diaries, and journals.

- Government documents.

- Newspaper articles from the period.

- Speeches and interviews.

- Photographs, artwork, and artefacts.

- Census data and statistics.

These sources provide firsthand accounts and evidence from the historical period itself.

Locate Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are works created by historians analyzing the past. They include:

- Academic books and articles.

- Scholarly journals.

- Documentaries and historical analyses.

- Biographies.

- Review articles.

Look for sources published by university presses or peer-reviewed journals for the most reliable information.

Take Effective Notes

As you research, organize your notes carefully:

- Record complete citation information for each source.

- Note page numbers for quotes and specific information.

- Summarise key points in your own words.

- Identify potential quotes to use in your paper.

- Mark connections between different sources.

Good note-taking will make outlining and writing much easier later on.

Evaluate Your Sources

Not all historical sources are equally reliable. Ask yourself:

- Who created this source and why?

- When was it created?

- Is there any bias or agenda that might affect its reliability?

- How does this source compare with others on the same topic?

- Has this source been peer-reviewed or vetted by historical experts?

To streamline your research process, consider checking out AI tools for history homework that can help organize your findings.

Crafting an Effective History Outline

With your research in hand, you’re ready to create an outline that will guide your writing process.

Elements of a Strong History Outline

A complete history outline includes:

- Thesis Statement: Your paper’s central argument is stated clearly and specifically.

- Main Points: The key ideas that support your thesis. These will become the topic sentences of your body paragraphs or sections.

- Supporting Evidence: Facts, quotes, and examples from your research that back up each main point.

- Analysis: Your interpretation of how the evidence supports your main points and overall thesis.

- Counterarguments: Alternative viewpoints you plan to address and refute.

Basic History Outline Format

Here’s a simple format to follow:

I. Introduction

A. Hook/attention grabber

B. Brief background on topic

C. Thesis statement

II. First Main Point

A. Supporting evidence

B. Analysis

C. Transition to next point

III. Second Main Point

A. Supporting evidence

B. Analysis

C. Transition to next point

IV. Third Main Point

A. Supporting evidence

B. Analysis

C. Transition to next point

V. Counterarguments

A. Alternative viewpoint

B. Refutation with evidence

C. Reinforcement of thesis

VI. Conclusion

A. Restatement of thesis

B. Summary of main points

C. Broader significance of your argument

Adjust the number of main points based on your assignment’s requirements and the complexity of your topic.

Tips for Outlining History Papers

- Be specific: Include enough detail in your outline to guide your writing, but don’t write whole paragraphs.

- Use parallel structure: If one main point begins with a verb, structure the others similarly.

- Balance your sections: Make sure each main point has roughly equal importance and supporting evidence.

- Arrange points logically: Consider chronological order, cause-and-effect relationships, or a progression from simple to complex ideas.

- Include transitions: Note how you’ll connect ideas between sections.

A well-structured outline provides the skeleton for your paper and makes the writing process much smoother.

The Anatomy of a History Essay

Understanding the components of a history essay will help you transform your outline into a polished paper.

Introduction

A strong introduction should:

- Hook your reader with an interesting fact, question, or anecdote.

- Provide necessary context about the historical period or event.

- Present a clear thesis statement that makes an arguable claim.

- Preview your main points (for longer papers).

- Establish why your topic matters historically.

Keep your introduction brief—about 5-10% of your paper length.

Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should:

- Begin with a topic sentence that connects to your thesis.

- Present one main idea with supporting evidence.

- Include at least one quote or specific piece of evidence from your sources.

- Analyze the evidence (don’t just report facts).

- End with a transition to the following paragraph.

The number of paragraphs varies depending on your assignment length and complexity. A standard five-paragraph essay might have three body paragraphs, while a research paper could have many more.

Conclusion

Your conclusion should:

- Restate your thesis (in different words).

- Summarise your main points.

- Explain the broader significance of your argument.

- Avoid introducing new evidence.

- End with a thought-provoking statement about the historical implications.

The conclusion typically accounts for 5-10% of your paper length.

Writing Compelling Historical Paragraphs

The paragraph is the building block of your history paper. Here’s how to craft effective ones:

Paragraph Structure

A standard historical paragraph follows this pattern:

- Topic sentence: States the main point of the paragraph.

- Context: Provides background information if needed.

- Evidence: Presents specific facts, quotes, or examples.

- Analysis: Explains how the evidence supports your point.

- Significance: Connects back to your thesis.

- Transition: Links to the following paragraph.

Example of a Historical Paragraph

Topic sentence: The Treaty of Versailles created economic conditions that fueled German resentment after World War I.

Context: When the treaty was signed in 1919, Germany was already struggling from the effects of the war.

Evidence: The treaty imposed reparation payments of 132 billion gold marks, which economist John Maynard Keynes criticized as excessive and potentially disastrous.

Analysis: These harsh financial penalties crippled the German economy and led to hyperinflation in the early 1920s.

Significance: The economic hardship created fertile ground for extremist political movements, including the Nazi Party.

Transition: Beyond economic penalties, the treaty also imposed territorial losses that further damaged German national pride.

How Many Paragraphs Per Page?

A typical history paper contains about 2-3 paragraphs per double-spaced page. However, content needs should determine paragraph length rather than arbitrary counts. Each paragraph should fully develop one idea before moving to the next.

Tips for Writing Effective Paragraphs

- Vary your paragraph length: Mix longer analytical paragraphs with shorter transitional ones.

- Use clear transitions: Connect paragraphs with phrases like “Similarly,” “In contrast,” “Furthermore,” or “As a result.”

- Stay focused: Each paragraph should develop only one main idea.

- Integrate quotes smoothly: Introduce quotes with context and explain their significance afterwards.

- Avoid excessive detail: Include only the historical facts relevant to your argument.

Well-crafted paragraphs make your paper more readable and your arguments more persuasive.

Structure and Format of History Papers

Proper formatting demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail. Most history papers follow these conventions:

General Formatting

- Double-spaced text.

- 1-inch margins on all sides.

- 12-point Times New Roman or similar font.

- Page numbers in the upper right corner.

- Title page (if required by your instructor).

Citation Styles

History papers typically use either:

Chicago Style (most common for history)

- Uses footnotes or endnotes for citations.

- Includes a bibliography at the end.

- Example: Smith argues that “the economic factors were paramount.”

MLA Style

- Uses parenthetical citations.

- Includes a Works Cited page.

- Example: Smith argues that “the economic factors were paramount” (Smith 42).

Always check with your instructor about preferred citation style.

Headings and Subheadings

For longer papers, using headings helps organize your content:

- Main headings: Centred, bold.

- Subheadings: Left-aligned, bold.

- Sub-subheadings: Indented, bold, followed by a period.

Tables and Figures

If your paper includes data:

- Number tables and figures sequentially.

- Provide a title for each.

- Cite the source underneath.

- Reference them in your text (e.g., “As shown in Figure 1…”).

Following proper formatting guidelines makes your paper more professional and easier to read.

Starting Strong: How to Begin Your History Essay?

The beginning of your paper sets the tone for everything that follows. Here are effective ways to start:

Attention-Grabbing Openings

- Surprising fact: “When Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, it directly freed very few enslaved people—yet it ultimately led to the end of slavery in America.”

- Relevant quotation: “Winston Churchill once remarked that ‘history is written by the victors.’ The aftermath of the Spanish Civil War demonstrates this principle with particular clarity.”

- Provocative question: “How might the Cold War have unfolded if the United States had not dropped atomic bombs on Japan?”

- Brief anecdote: “On a sweltering July day in Philadelphia, 56 men committed what many considered an act of treason by signing their names to a document declaring independence from the most powerful empire in the world.”

- Historical paradox: “The same democratic principles that inspired the French Revolution also helped justify the Reign of Terror that followed.”

Providing Context

After your opening hook, provide just enough background information for readers to understand your topic:

- Period

- Key figures

- Essential events leading up to your focus

- Previous historical interpretations (if relevant)

Keep this section brief—you want to get to your thesis quickly.

Crafting a Strong Thesis Statement

Your thesis should:

- Make a specific, debatable claim.

- Indicate the structure of your argument.

- Be provable with historical evidence.

- Express an original perspective.

Weak thesis: “World War II had many causes.” Strong thesis: “While economic factors contributed to the outbreak of World War II, Hitler’s expansionist ideology and the failure of appeasement policies were more significant in triggering the conflict.”

A compelling introduction draws readers in and clearly establishes your paper’s arguments.

Research Paper Fundamentals for History Students

History research papers require a more comprehensive approach than shorter essays. Here’s what you need to know:

Choosing a Manageable Topic

Select a topic that:

- Interests you personally.

- Has sufficient available sources.

- It is specific enough to cover thoroughly.

- Allows for original analysis.

Narrow broad topics by focusing on:

- A specific period.

- A particular region or location.

- A single aspect of a larger event.

- A specific group of people.

For example, instead of “The Civil Rights Movement,” focus on “The Role of Women in the Montgomery Bus Boycott.”

Developing a Research Question

Frame your topic as a question to guide your research:

- “How did Allied bombing affect German civilian morale during World War II?”

- “To what extent did economic factors influence Southern secession before the Civil War?”

- “How did Native American tribes respond differently to European colonization?”

A good research question requires analysis, not just fact-finding.

History Research Paper Structure

A typical history research paper includes:

- Introduction: Establishes topic, context, and thesis.

- Literature Review: Summarises previous historical scholarship on your topic.

- Methodology: Explains your research approach and sources (for advanced papers).

- Background: Provides necessary historical context.

- Body Sections: Presents evidence and analysis, organized by subtopic.

- Counterarguments: Addresses alternative interpretations.

- Conclusion: Synthesises findings and explains significance.

- Bibliography/Works Cited: Lists all sources.

- Appendices: Includes supplementary materials if necessary.

Sample History Research Paper Outline

I. Introduction

A. Hook about the significance of the Boston Tea Party

B. Brief context of colonial tensions with Britain

C. Thesis: The Boston Tea Party represented a protest against taxation and a deliberate strategy to unite colonial resistance.

II. Literature Review

A. Traditional interpretations

B. Recent scholarship

C. Gaps in current understanding

III. Background

A. British taxation policies after 1763

B. Colonial resistance movements

C. East India Company’s tea monopoly

IV. The Planning of the Tea Party

A. Role of the Sons of Liberty

B. Evidence of coordination with other colonies

C. Strategic timing

V. Execution and Immediate Consequences

A. Participants and their actions

B. Colonial reactions

C. British response

VI. Long-term Significance

A. Impact on colonial unity

B. Influence on subsequent protests

C. Role in the path to revolution

VII. Counterarguments

A. Spontaneous protest interpretation

B. Economic rather than political motivations

C. Refutation of these views

VIII. Conclusion

A. Restatement of thesis

B. Summary of evidence

C. Broader historical significance

This outline provides a solid structure for analyzing a historical event while clearly focusing on your thesis.

Examples and Templates for History Papers

History Essay Outline Example

Topic: The Impact of the Printing Press on the Protestant Reformation

I. Introduction

A. Hook: Before the printing press, religious texts were controlled by Church authorities; within decades of Gutenberg’s invention, religious ideas spread rapidly across Europe.

B. Background: Brief overview of Gutenberg’s press (c. 1440)

C. Thesis: The printing press was essential to spreading Protestant ideas because it democratized access to religious texts, enabled rapid dissemination of reformist writings, and undermined Church authority over information.

II. Democratization of Religious Texts

A. Evidence: Translation of the Bible into vernacular languages

B. Evidence: Decreasing cost of book production

C. Analysis: How wider access changed the relationship between people and scripture

III. Rapid Dissemination of Reformist Writings

A. Evidence: Luther’s 95 Theses and pamphlets

B. Evidence: Statistics on the number of copies printed

C. Analysis: How print technology outpaced Church censorship efforts

IV. Undermining of Church Authority

A. Evidence: Competing interpretations in print

B. Evidence: Satirical prints and propaganda

C. Analysis: Shift in information control from the Church to the printers

V. Counterargument: Other Factors in Reformation

A. Political tensions with Rome

B. Economic factors

C. Refutation: Why are these factors required to become effective

VI. Conclusion

A. Restatement of thesis

B. Summary of key points

C. Broader significance: How print technology continued to shape religious and political developments

Historical Research Paper Example

Introduction from a Paper on the Cuban Missile Crisis:

The thirteen days in October 1962 that came to be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than any other event in history. As Soviet ships carrying missile components steamed toward Cuba and American naval forces prepared to intercept them, leaders on both sides faced decisions that could potentially trigger a catastrophic conflict. While traditional accounts emphasize President Kennedy’s firm stance against Soviet aggression, recently declassified documents from American and Soviet archives reveal a more complex picture of the crisis resolution. This paper argues that back-channel diplomacy and mutual concessions played a more significant role in peacefully resolving the Cuban Missile Crisis than the official public positions of either superpower. By examining diplomatic communications, meeting transcripts, and memoirs from key participants, this research demonstrates how unofficial negotiations created the space for compromise that official rhetoric had seemingly made impossible.

Historical Paragraph Example

The Great Depression fundamentally transformed the American political landscape and citizens’ relationship with their government. Before 1929, federal economic intervention was limited, and many Americans viewed such involvement with suspicion. However, as unemployment reached 25% by 1933, public attitudes shifted dramatically. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs represented an unprecedented expansion of federal authority, establishing social security, unemployment insurance, and federal works projects. As historian David Kennedy notes, “The New Deal forever changed the relationship between the citizen and the state in America.” This transformation met significant resistance from conservatives and the Supreme Court initially, but the depth of the economic crisis ultimately convinced many Americans that government intervention was necessary. The legacy of this shift continues to shape American politics today, as debates about the proper role of government often reference the precedents established during this pivotal period.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them?

Even experienced writers make mistakes in history papers. Here’s how to avoid the most common ones:

Presentism

Mistake: Judging historical actors by modern standards and values.

Example: “Medieval doctors were incompetent because they didn’t understand germ theory.”

Solution: Evaluate historical figures within their own context. Consider the knowledge, beliefs, and constraints of their time.

Overreliance on Secondary Sources

Mistake: Using only textbooks and modern interpretations without consulting primary sources.

Example: Writing about the American Revolution based solely on modern historians’ books, without examining documents from the period.

Solution: Balance secondary sources with primary materials. Let historical actors speak for themselves through their letters, speeches, and writings.

Vague Thesis Statements

Mistake: Creating a thesis that’s too broad or merely factual.

Example: “World War I had many important consequences.”

Solution: Make specific, arguable claims requiring evidence and analysis.

Chronological Listing

Mistake: Simply recounting events in order without analysis.

Example: “First A happened, then B happened, followed by C.”

Solution: Organize around themes, causes, or impacts rather than strict chronology. Explain why events matter, not just when they occurred.

Unsupported Generalizations

Mistake: Making broad claims without specific evidence.

Example: “All peasants opposed the French Revolution.”

Solution: Qualify your statements and provide specific examples. Use words like “many,” “some,” or “often” instead of absolutes.

Weak Introductions and Conclusions

Mistake: Beginning with overly general statements or ending without significance.

Example: “Throughout history, wars have occurred for many reasons.”

Solution: Start with specific, engaging information and end by explaining why your argument matters in understanding history.

Improper Citation

Mistake: Inconsistent citation format or failure to cite sources.

Example: Mixing Chicago and MLA styles or not citing paraphrased information.

Solution: Choose one citation style and apply it consistently. When in doubt, cite your source.

Avoiding these common errors will strengthen your history papers and help you communicate your ideas more effectively.

Finalizing Your History Paper: Editing and Submission

After drafting your paper, take time to refine it through careful editing and formatting.

Revision Checklist

- Structure and Argument:

- Does your thesis make a clear, arguable claim?

- Do all paragraphs relate to and support your thesis?

- Is your evidence persuasive and relevant?

- Have you addressed potential counterarguments?

- Content and Analysis:

- Are factual claims accurate and supported by sources?

- Have you explained the significance of your evidence?

- Do you analyze rather than just describe historical events?

- Are there any gaps in your argument that need addressing?

- Writing and Style:

- Is your language clear and concise?

- Have you varied your sentence structure?

- Are transitions smooth between paragraphs?

- Have you defined any specialized terminology?

- Citations and formatting

- all sources properly cited?

- Is your bibliography formatted correctly?

- Does your paper meet all formatting requirements?

- Have you included page numbers and other required elements?

Peer Review

Having someone else read your paper can provide valuable feedback:

- Ask specific questions about areas of concern

- Be open to constructive criticism

- Consider reading your paper aloud to catch awkward phrasing

Final Proofreading

Check for:

- Spelling and grammar errors.

- Consistency in tense (usually past tense for history papers).

- Correct use of names, dates, and terminology.

- Proper punctuation, especially in quotations.

Submission Guidelines

Before turning in your paper:

- Follow all guidelines for file format and submission method.

- Include any required cover sheets or title pages.

- Keep a backup copy for your records.

- Submit before the deadline to avoid technical problems.

Taking time for thorough revision and careful submission demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail qualities that history professors value.

Not confident in your historical accuracy? Double-check your facts with a reliable history AI tool designed specifically for history students.

Glossary of Key Terms for Writing History

This Glossary provides concise definitions of key terms used throughout this guide and commonly encountered in academic history. Mastering these terms will enhance your comprehension and allow you to engage more precisely with historical texts and assignments.

Analysis: The intellectual process of breaking down a complex historical topic, event, or source into its constituent parts to understand their relationships, significance, and how they contribute to a larger whole. In history, analysis moves beyond mere description (what happened) to explain how or why something happened, and its consequences.

Argument: The central claim, assertion, or interpretation a historical paper puts forward and defends with Evidence and reasoning. It is the answer to a historical question.

Bibliography: An alphabetized list, typically found at the end of a research paper or book, detailing all the sources (books, articles, documents, etc.) consulted by the author during the research process.

Chicago Manual of Style (CMS): A widely adopted citation and formatting style used in the humanities, particularly in history. It typically employs footnotes or endnotes for in-text citations and a bibliography.

Citation: A formal reference to a source of information used within a paper. Citations credit the original author and allow readers to locate the source.

Conclusion: The final section of an essay or research paper. It typically restates the thesis in new words, summarises the main supporting arguments, and offers final thoughts on its broader significance or implications.

Context (Historical): The specific circumstances surrounding a historical event, idea, or individual. This includes the social, political, economic, cultural, intellectual, and environmental conditions of the time and place, which are essential for accurately understanding and interpreting the past.

Evidence: Information drawn from historical sources (such as documents, artefacts, statistics, or eyewitness accounts) that is used to support or refute a historical claim or argument.

Historiography: The study of the writing of history and of historical interpretation. It examines how historians have approached particular topics, the theories and methods they have used, the debates among them, and how interpretations of the past have changed over time.

Introduction: The opening section of a paper. It aims to engage the reader, provide necessary background information or context, and present the paper’s thesis statement, often outlining the main points.

Outline: A structured plan for a piece of writing that organizes the main ideas, sub-points, and supporting Evidence in a hierarchical order (e.g., using Roman numerals, letters, and numbers). It serves as a blueprint for the paper.

Paraphrase: To restate information or ideas from a source in your own words and sentence structure, while accurately conveying the original meaning. A paraphrase must always be cited.

Plagiarism is presenting someone else’s work, ideas, or words as your own without proper acknowledgement or citation. It is a serious breach of academic integrity.7

Primary Source: A document, artefact, or other piece of Evidence created during the historical period being studied, or by an individual who directly participated in or witnessed the events. Examples include letters, diaries, official records, photographs, tools, and contemporary newspaper accounts.

Prompt (Assignment Prompt): The specific question, topic, or instructions an instructor provides for a written assignment, outlining the task to be completed.6

Quote/Quotation: The exact words taken directly from a source, enclosed in quotation marks (or set as a block quote if longer) and properly cited.

Revision: The process of re-examining and making substantive changes to a paper draft to improve its argument, structure, clarity, use of Evidence, and overall effectiveness. It goes beyond simple proofreading.

Secondary Source: A work that interprets, analyses, or discusses historical events or primary sources. Secondary sources are typically written by historians or scholars after the events, based on their research and analysis of primary materials and other secondary works. Examples include scholarly books and academic journal articles.6

Thesis Statement: A clear, concise, and arguable statement, usually appearing in the Introduction of a paper, that presents the main argument, interpretation, or position that the paper will develop and support with Evidence.

Topic Sentence: A sentence, typically placed at or near the beginning of a body paragraph, that states the main idea or argument of that paragraph and links it to the overall thesis of the paper.

This Glossary serves as more than just a list of definitions. It is a tool for promoting clarity and precision, not only in understanding this guide but also in your historical thinking and writing.

By defining these terms clearly, the aim is to make this disciplinary language accessible. This empowers students to use these concepts confidently and accurately, essential for participating effectively in academic discourse in history.

It helps bridge any perceived gap between straightforward communication and the necessary precision of scholarly language.

Conclusion: Becoming a Confident History Writer

Writing history papers is a skill that improves with practice. Each outline you create and paper you write builds your abilities as a historian and critical thinker.

The process we’ve outlined—from understanding your assignment and conducting research to crafting an outline and writing a polished paper—provides a roadmap for success in any history course. By following these steps, you can transform from a student who struggles with history writing to one who confidently approaches assignments.

Remember that good historical writing isn’t just about reporting facts. It’s about making connections between events, analyzing causes and effects, and developing your own interpretation based on evidence. These analytical skills extend beyond the history classroom and will serve you well in many academic and professional contexts.

As you gain experience, you’ll develop your own process and style. You might prefer to create very detailed outlines, or perhaps you’ll discover that starting with a research question works better for your thinking process. The key is to find an approach that helps you organize your thoughts effectively and produce clear, persuasive historical writing.

Writing about history allows us to understand what happened in the past and also why it matters today. By mastering the skills in this guide, you’re not just learning to write better papers—you’re learning to think more deeply about the forces that have shaped our world. And that’s what the study of history is truly about.